Think about the last time you made a decision about your finances.

Now think about the end result (outcome) of that decision.

If the end result was unsatisfactory, I’m confident you would have considered it to be a poor decision.

Comparably, if the end result was satisfactory, you’ll probably be thinking that you made an excellent decision.

You may be right or you may be wrong, but what you’ve just done is called resulting, an idea that Annie Duke discusses in her book How To Decide.

Resulting happens when we evaluate the quality of our decisions based on the outcome.

This is a widespread occurrence, however, the issue is we often learn the wrong lessons by using this method to evaluate our decisions.

Some financial decisions we make will be among the most important decisions we make in our lifetime, so it’s critical to focus on ways to make those decisions as effectively as possible.

Even if you outsource your finances to financial advisers, accountants and lawyers, you’re still going to have to pick your professionals, answer questions regarding strategy and ultimately authorise the execution of anything proposed. So whichever way you look at it, you don’t get to escape making decisions regarding your finances.

Something else I’d like to stress is not making a decision is as much a decision as any other option on the table. Greg McKeown put it succinctly in his noteworthy book Essentialism: “when we surrender our ability to choose, something or someone else will step in to choose for us”.

In this article, I explore reasons why we should improve our decision-making skills, overcoming decision-making paralysis, and step you through building your own framework for making financial decisions in your own life.

Why should we consider improving our decision-making skills?

“For too long, we have overemphasized the external aspect of choices (our options) and underemphasized our internal ability to choose (our actions). This is more than semantics. Think about it this way. Options (things) can be taken away, while our core ability to choose (free will) cannot be.”

Greg McKeown

Sometimes we make an excellent decision and it turns out poorly and other times we make a poor decision that somehow turns out well. This doesn’t mean that the process is repeatable or even something we should learn from.

I have purchased shares in a company before with little thought and for some reason, it went up over 100%. I have also put a lot of time into learning about a company before buying shares, however, nothing in my decision-making process prepared me for how badly the company performed. I’m sure investors have seen a million variations of that scenario throughout history, but if we explore our decision-making process, we can ensure that our overall financial position is constructed from a sound process.

“If you’re like most people, it’s easier to blame bad luck for a bad outcome than it is to credit good luck for a good outcome.”

Annie Duke

One thing that Duke suggests doing to evaluate when this happens is to list three reasons why you had a good/bad outcome despite a good/poor decision-making process. In other words, “what were some of the things outside of your control or things you didn’t anticipate in your original decision process?”

Common pitfalls when we make financial decisions

So what are some of the most common mistakes we make when making financial decisions? It’s often helpful to learn from these mistakes because making the wrong decisions when it comes to our finances can cost us dearly over our lifetime.

We’re too trusting.

We don’t read the fine print.

We think we know something others don’t.

We focus on returns over fees.

We get greedy.

We don’t common sense check the details.

Of course, sometimes we can steer clear of all the above points and still have a bad outcome with one of our investments due to a factor completely out of our control. This is why I talk about the importance of diversification in your finances so often, but that’s a whole different discussion.

There are so many ways for things to go wrong when making decisions it can become overwhelming to think about them. After all, you’re here to make a decision right?

What are some ways to make sounder financial decisions?

Now we’ve thought about why we need to improve our financial decision-making skills and where we can go wrong, let’s explore some different methods to improve our decisions.

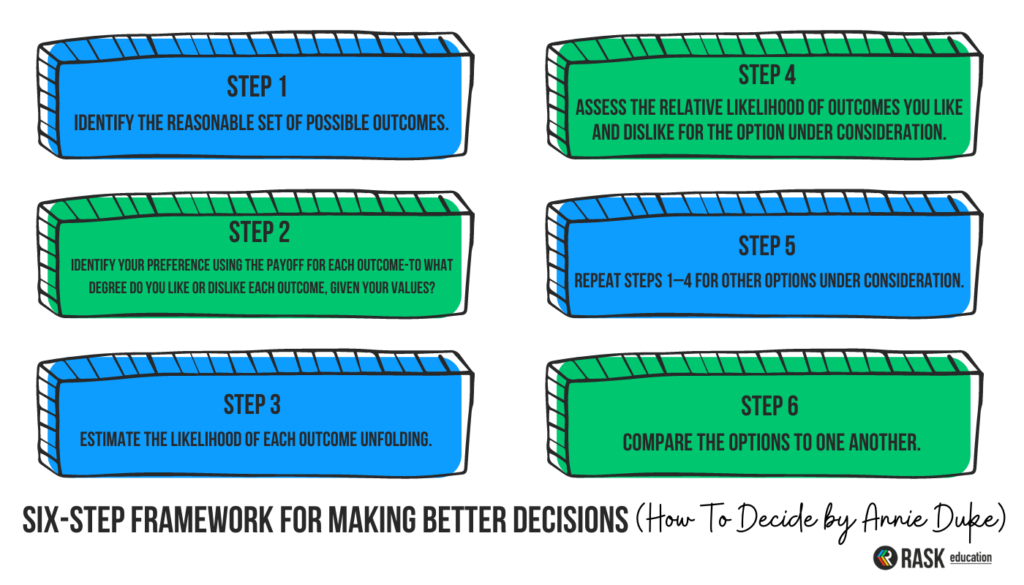

Duke proposes a six-step framework for making better decisions, by fully evaluating each potential option and their reasonable outcomes.

Step 1 – Identify the reasonable set of possible outcomes.

Step 2 – Identify your preference using the payoff for each outcome—to what degree do you like or dislike each outcome, given your values?

Step 3 – Estimate the likelihood of each outcome unfolding.

Step 4 – Assess the relative likelihood of outcomes you like and dislike for the option under consideration.

Step 5 – Repeat Steps 1–4 for other options under consideration.

Step 6 – Compare the options to one another.

Let’s apply this framework to the following scenario. You have just been given $10k with no strings attached. You are free to do whatever you wish with it, however, the giver has strongly recommended that you invest it for your future.

What are the potential options on the table?

If you’re new to investing you might not even be aware of all the different options available to you, which would limit your range of choices.

Here are just a few options to consider:

Do nothing – it might get too hard to make a decision and you decide to just leave the money in the bank.

Spend it – maybe you’ve got something in mind right now for these funds.

Invest in ETFs – you’ve been interested in investing for a while, so decide to start investing in ETFs.

Invest in property – you have always been interested in property and this is the perfect leg up.

Add in any other options that come to mind for this money.

Now let’s take the do nothing option and think about a reasonable set of possible outcomes for it.

- You leave the money under the bed and when the market crashes you feel very clever.

- You leave the money under the bed and miss a 10-year bull market.

- You leave the money in a savings account and are happy to earn 1% interest on your cash.

- You leave the money in a savings account and look back in 10 years, regretting that you never made the decision to invest.

- You leave the money in a savings account and can use the money to start a business in a few years time.

- You leave the money to your children in your will and never get to enjoy it.

Add in any of your own outcomes to the do nothing option above and have a think about the potential outcomes that would be relevant to the other options (spend it, invest in ETFs and invest in property).

Then run through Duke’s six-step framework to evaluate each outcome. This will probably take you some time and research, but will force you to critically examine each option on the table.

By using this method you’ll go much deeper than a pros v cons list ever could, and you’ll have a record of all the factors that you considered at the time of making your decision.

This will be a practical document for you to refer back to once your decision reaches an outcome, to fully assess whether you made an objectively good or poor decision and whether you could have reasonably expected the overall outcome.

Building your own decision-making framework

Now that we’ve explored some ways to improve your decisions, how can we turn that into a personalised decision-making framework?

Like anything, making decisions is a profoundly personal activity, and I may make a very different decision with what to do with my $10k compared to what you would do. There are so many factors that go into the decisions we make, that is, it can be difficult to compare the decision-making skills of two different people.

The way I’ve decided to work on improving my own decisions is by creating a template that I work through when assessing a major decision.

I’ve included the following components on my own template:

- What is the decision to be made?

- When do I need to make a decision by?

- What are the options on the table?

- What are the potential outcomes of each option?

- What is my preferred outcome and the likelihood of that occurring?

- What is the likelihood of an undesirable outcome occurring?

- Is there anything I can do to mitigate the chances of an undesirable outcome occurring?

- What impact will these potential outcomes have on my family and friends?

- Does my decision align with my values and will I be happy with who I am even if it turns out badly?

- What can I do to improve the chances of reaching a successful outcome after making my decision?

I’d encourage you to create your own framework detailing the questions you’d like to work through for the next big decision that you make. Don’t worry if it’s not complete, this will be an ever-evolving process that you refine and adapt throughout your lifetime.

The most important step after running though your own decision-making framework is to actually make and execute the decision. There’s no point going through all the effort and then falling back to the default trap of making no decision. If no decision is the option you choose, make sure you can write down the reasons why you chose that and schedule a calendar invite to revisit in a few months time.

Overcoming decision-making paralysis

If you’ve made it this far, you’ll probably be asking yourself how you can possibly make a decision after reading all that. A six-step process to evaluate every option’s outcomes?! Give me a break! I’ll never get anything done!

The truth of the matter is most decisions don’t need that process, and we perform them in a matter of seconds (or sometimes minutes).

It all comes down to considering the impact of getting the decision wrong.

If it’s a low-cost decision like what to wear, what to eat, what to watch, and what to drink, we can rapidly speed up the pace at which we make the decision.

If we assess the decision as having a bigger impact on our lives, then we should spend much more time on it.

If we go back to the decision of what to do with the $10k we were given, we should be spending much more time on that decision, than if we were deciding whether to get a coffee or not.

If I get the decision with the $10k right I can help set myself up for retirement. If I get it wrong, the money could disappear in a flash.

If you invested $10,000 in the stock market over 50 years, with an average annual interest rate of 7% and no additional contributions, you would end up with $327,804.

That’s worth working on your decision-making skills for, isn’t it?

I hope this deep dive into financial decision-making has prompted you to think more critically about your own processes, and I’d highly encourage you to explore the resources provided to learn more.

Reading just one of these books is a profoundly wise decision (if I can say so myself)!

Resources to improve your decision-making skills

- How To Decide: Annie Duke

- Essentialism: Greg McKeown

- The Psychology of Money : Morgan Housel

- Financial News During COVID-19 | Rask Australia

- Ep. 36. Catching Our Behavioural Biases | Rask Australia

- The Psychology and Neuroscience of Financial Decision Making

- How to Make Decisions – Decision-Making Tools From MindTools.com