Many stock market indices, like Australia’s S&P/ASX 200 and the USA’s Dow Jones Industrial Average, are expressed in points and not dollars ($).

For example, a reporter might say, “The Dow Jones fell 20 points today” or “The ASX 200 closed at 6,000 points”.

What is the ASX 200 and Dow Jones?

The ASX 200 and Dow Jones are types of stock market indices that are designed to track particular markets.

For example, the S&P/ASX 200 is an Australian stock market index, created and maintained by Standard & Poor’s (S&P). It tracks the value of the 200 largest public companies ranked by their market capitalisation, adjusted for the shares that are actually available on the market.

We’ll get to market capitalisation in a minute. In the meantime, if you’re interested in learning more about the ASX 200 and/or Dow Jones, including what they’re used for and which companies are in them, visit our blog posts: What is the ASX 200? and What is the Dow Jones?

Other popular stock market indices you may have heard of are the USA’s S&P 500 and NASDAQ composite, Britain’s FTSE 100, the Japanese Nikkei 225 and Hong Kong’s Hang Seng. Each of these indices track the performance of the largest companies listed on the respective stock exchanges (i.e. countries).

Why do they use “points”?

The reason most indices use points comes back to the way they are calculated.

For example, in simple terms, the ASX 200 is built using the market capitalisation of the ASX’s 200 largest companies (it has some other rules).

Market capitalisation simply equals share price multiplied by the number of shares on issue (share price x number of shares).

For example, if Orange Phones has 200 shares currently priced at $5, its market capitalisation is $1,000 (200 x $5).

If an index is weighted according to market capitalisation, such is the case with the ASX 200, this simply means that the companies with the largest market capitalisation make up the largest part of the index.

Many stock market indices are ‘adjusted’ for changes which the companies in the index might undergo (e.g. spin-offs, stock splits, etc).

For example, when Australian infant formula company Bellamy’s was bought by a Chinese company late last year, its shares were no longer listed on the ASX. As a result, Bellamy’s was removed from the ASX 200 index. Despite this, the ASX 200’s ‘level’ should have stayed the same to be consistent — in order to do so, it must be adjusted by a number that’s NOT a dollar value.

If S&P didn’t make these ‘adjustments’, the indices might jump up and down violently and not be representative of the entire stock market.

To account for these types of changes, the indices are adjusted using what’s called a ‘divisor’. It’s the tiny number that makes the index level smooth for changes in the company’s corporate structure.

Because the divisor is not in dollars ($), the index shouldn’t be in dollars either.

“The Dow Jones collapsed 400 points!”

Let’s use the Dow Jones as an example which, unlike the ASX 200, is a price-weighted index.

What that means is the share with the highest price is given the most influence over the index’s day-to-day movements.

For example, if a $1,000 share and a $10 share were both included in the index, the higher priced share ($1,000) would have a much larger influence on the index — even if the company with a $10 share price had 200 times more shares on issue (making it a larger company).

The Dow’s formula is simply the price of all shares in the index divided by the ‘Dow divisor’, which is a number less than one.

In April 2019, the Divisor was 0.14744568353097. Meaning, a $1 share price movement in the companies included in The Dow resulted in The Dow moving 1/0.14744568353097 = 6.782 points.

So, if a news headline were to read something like, “The Dow dropped 400 points yesterday”, this means that the share prices of the 30 companies that make up the Dow Jones would have, as a whole, fallen 400 x 0.14744568353097 = $59.

How do I invest in the ASX 200?

Investors are able to get exposure to many stock market indices through something known as ETFs.

ETF (not EFT!) stands for Exchange Traded Fund.

ETFs are:

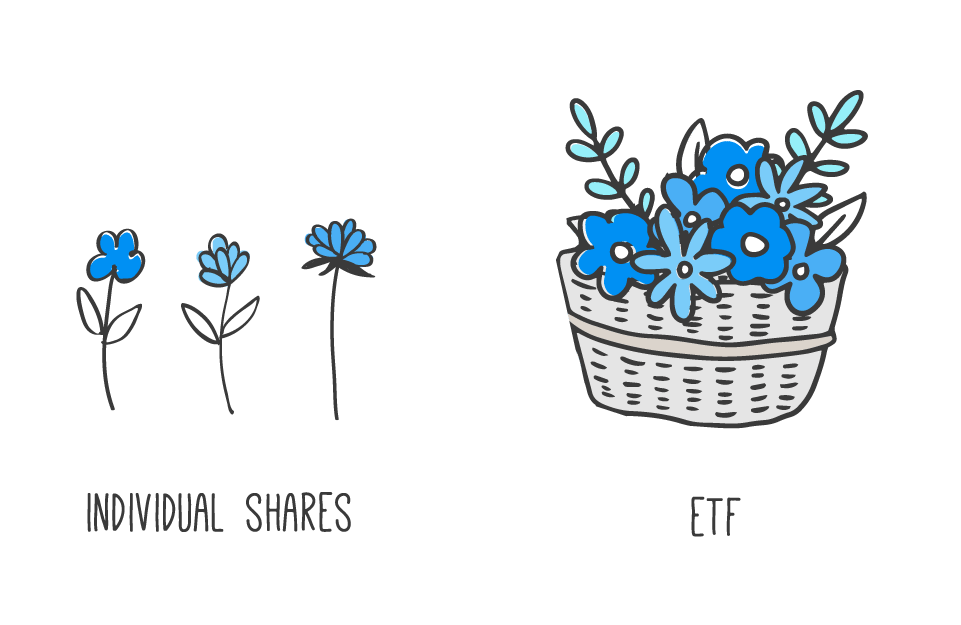

- A bunch of investments (e.g. shares) put in one basket

- You buy the ‘basket’ just as you would any other share on the stock exchange

- The company that operates the ETF collects a small yearly fee, taken out of your investment automatically

Just imagine you walk into a florist. Instead of buying one stem or flower (a share), the florist puts together a posy or ‘basket’ of flowers (an ETF). You can buy the entire basket.

These ‘baskets’ can be designed to track the performance of particular stock market indices. For example, there are ETFs that track the ASX 200 index, the S&P 500 index, the NASDAQ composite, and so on.

When we say that an ETF “tracks” a particular index, this means that the professional funds management company (otherwise known as the ETF issuer) will buy similar investments (e.g. shares of companies) to the index in an attempt to closely match the index’s return.

Imagine the florist is the ETF manager who is trying to create a basket of flowers according to what is the most popular and valuable.

How to invest in ETFs

Take our free Beginner’s ETF Investing Course!

In our Beginner ETF Investing Course, we’ll answer the 10 most common questions Australians have about ETFs, including what they are, why you might use them, what you need to tell your accountant, and more.

Then, we’ll take you through 5 steps for getting started and what you can expect.

All this for a grand total of $0… sounds like a pretty great deal if you ask us!

So, what’re you waiting for? Click here to enrol now.

[ls_content_block id=”27643″]